Featured Articles

The Hauser Report: Remembering Bill Russell (1934-2022)

Bill Russell, an inspirational figure and one of the most important athletes in the history of sports, died on July 31 at age 88.

Russell revolutionized the game of basketball. Standing 6-feet-9-inches tall and weighing a lithe 220 pounds, he originated a new style of play. Blocking shots and firing pinpoint passes to initiate fast breaks after grabbing rebounds, playing tenacious defense and transforming the center position from a haven for slow lumbering giants to one of fluidity and motion.

On the court, Russell lived by the mantra, “Professional athletes are not paid to play. They’re paid to win.” He was a two-time All-American at the University of San Francisco, where he led the Dons to 55 consecutive victories and two NCAA championships. Next, he spearheaded the United States basketball team’s gold-medal performance at the 1956 Olympics. Then he became the cornerstone of the greatest dynasty in the history of sports.

During a 13-year playing career that began in 1956, Russell led the Boston Celtics to eleven NBA championships. A half-century later, Boston’s eight consecutive titles from 1959 to 1966 remain unmatched in professional sports, surpassing the uninterrupted reigns of the New York Yankees (1949 to 1953) and Montreal Canadians (1956 to 1960).

Russell was a five-time league MVP and 12-time All-Star. He ended his career with 21,620 rebounds (second most in NBA history) and averaged a mind-boggling 22.5 rebounds per game. Once, he pulled down 51 rebounds in a single contest. Statistics for blocked shots weren’t kept when he played. But it’s likely that Russell blocked more shots than anyone else in NBA history. He also averaged 15.1 points and 4.3 assists per game.

His confrontations with Wilt Chamberlain from 1959 through 1969 constituted one of sports’ most storied rivalries.

But as Steve Kerr recently stated, “What Bill Russell did for his country and for society and the African American community dwarfs what he accomplished on the court.”

Harry Edwards (who rose to prominence as the architect of the 1968 Olympic protest movement) called Russell “the heir to Jackie Robinson’s struggle.”

When the Celtics beat the St. Louis Hawks in seven games to win the NBA championship in Russell’s first season, he was the only black player on either team. He was also one of the first athletes to use his celebrity status to confront racism.

Russell was with Martin Luther King Jr at the historic 1963 March on Washington. That same year, he went to Jackson, Mississippi in the aftermath of Medgar Evers’ assassination to carry on Evers’ work. He actively supported. the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar viewed Russell as one of his most important role models and recalled, “Some of the things that scared me and bothered me about race relations in America were things that he addressed. He gave me a way to speak about it that had all of the elements of trying to make something better rather than just being angry.”

Russell was also the first Black man to serve as head coach in a major American professional sports league.

In the early-1920s, running back Fritz Pollard was the head coach of the Akron Pros in the newly-formed National Football League. But Pollard and the league’s other nine Black players were removed from the NFL at the end of the 1926 season as the league began to gain a following. Four decades later, John McLendon coached briefly in the American Basketball League (which folded after one season) and American Basketball Association (which lasted for nine campaigns). But at the time, these leagues were secondary institutions.

Russell stepped into an entirely different situation. In 1966, Red Auerbach retired as coach of the Celtics after eight straight championships. In his role as general manager, he designated Russell as his successor. Russell then won two NBA championships as a player-coach and two more in the three seasons that followed his retirement as a player.

I was privileged to interact with Russell on several occasions.

The first came when I was 15 years old and in high school. In those days, NBA teams played doubleheaders at the old Madison Square Garden on 8th Avenue and 49th Street. And security was light. I’d buy a balcony ticket and a program, walk down a stairway to position myself outside the dressing rooms (which were in close proximity to one another), and ask for autographs as the players came in.

On this occasion, the Knicks were playing the Celtics in the second game of a doubleheader. In addition to my program, I’d brought full-page color photos of Russell and Celtics guard Sam Jones that I’d torn from Sport Magazine in the hope that I could get them signed.

Russell was adamant about not signing autographs. I didn’t know that at the time. Suddenly, he appeared, carrying a large gym bag. The vision of a giant eagle flashed through my mind.

I approached him and held out the photo.

“Mr. Russell. Could you sign this for me.”

“I don’t sign autographs.”

“Please.”

I don’t know why what happened next happened.

Wordlessly, Russell took the pen and photo from my hand . . . And signed.

Decades later, I was talking with him at the screening of an HBO documentary entitled Bill Russell: My Life, My Way. I’d come to know him better by then as a consequence of having interviewed him while researching Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times.

Russell complimented me on the book. Then I told him about the autograph and he cackled his famous cackle.

“So you were the one,” he said.

My records show that I interviewed Russell for the Ali biography on November 21, 1989. At the start of the interview, he told me, “I don’t like doing interviews. The only reason I’m talking with you is that Muhammad asked me to.”

“I never saw him fight,” Russell said of Ali. “I would never go to a fight. I just wouldn’t. I went to one a long time ago and I told myself I’d never go back. They’re much cleaner on television.”

We talked about the idea (floated in 1971) that Ali and Wilt Chamberlain engage in a prizefight.

“I can’t speak for Wilt,” Russell noted. “I just know that I personally would never challenge a champion in his field of expertise. I would never get in a boxing ring with Ali or on the football field with Jim Brown or on a track with Carl Lewis. I would never impose my thoughts or motivations on someone else. But for me personally, that’s just not the way I am.”

The heart of our interview concerned a meeting that had taken place in Cleveland twenty-two years earlier. On April 28, 1967, Ali had refused induction into the United States Armed Forces. On May 8, he was criminally indicted. In early June (shortly before his trial began), ten of the most prominent black athletes in America met with Muhammad to discuss his options.

Recalling that day, Russell told me, “I got a call from Jim Brown, who said that Ali was out there by himself and that we should support him in whatever he chose to do. So that was it, really. I didn’t go to Cleveland to persuade Muhammad to join or not join the Army. We were just there to help, and I was struck by how confident he was, how totally assured he was that what he was doing was right.

“I never thought of myself as a great man,” Russell continued. “I never aspired to be anything like that. I was just a guy trying to get through life. But in Cleveland, and many other times with Ali, I saw a man accepting special responsibilities, someone who conducted himself in a way that the people he came in contact with were better for the experience. Philosophically, Ali was a free man. Besides being probably the greatest boxer ever, he was free. And he was free at a time when historically it was very difficult to be free no matter who you were or what you were. Ali was one of the first truly free people in America.”

Not long after the Cleveland meeting, Russell spoke publicly about Ali’s draft status for the first time.

“I envy Muhammad Ali,” Russell said. “He faces a possible five years in jail and he has been stripped of his heavyweight championship, but I still envy him. He has something I have never been able to attain and something very few people I know possess. He has an absolute and sincere faith. I’m not worried about Muhammad Ali. He is better equipped than anyone I know to withstand the trials in store for him. What I’m worried about is the rest of us.”

In honoring Bill Russell with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011, Barack Obama proclaimed, “Bill was someone who stood up and insisted on dignity. He stood up for the rights and dignity of all men.”

Bill Russell was a great man. And a good one.

Thomas Hauser’s email address is thomashauserwriter@gmail.com. His most recent book – Broken Dreams: Another Year Inside Boxing – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism. In 2019, he was selected for boxing’s highest honor – induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

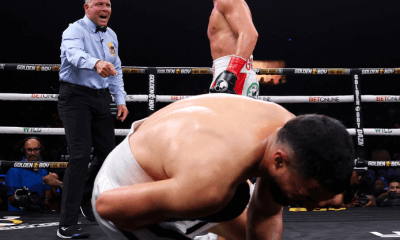

Featured Articles2 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision

-

Featured Articles6 days ago

Featured Articles6 days agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles4 days ago

Featured Articles4 days agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

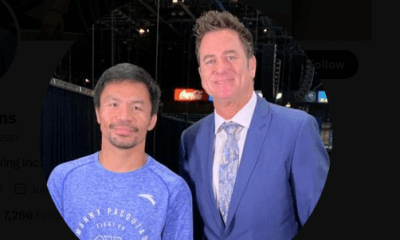

Featured Articles2 weeks agoFrom the Boondocks to the Big Time, The Wild Saga of Manny Pacquiao’s Sidekick Sean Gibbons