Featured Articles

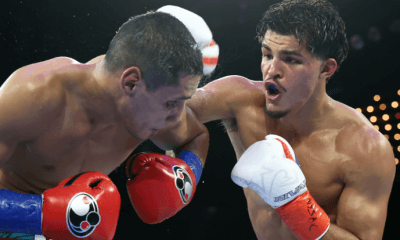

Lionell Thompson and the Afflictions of a ‘B-side’ Fighter

“Lionell ‘Lonnie B’ Thompson is a former professional boxer…” So reads the opening sentence of a blurb about him that popped up on the internet.

Except it’s wrong. Thompson isn’t a former boxer – his career isn’t dead, just dormant. It’s been dormant for more than three years, a prolonged gap in his boxing timeline that actually isn’t all that unusual for a “B-side” fighter. And the professional boxing career of Lionell “Lonnie B” Thompson has been quintessentially B-side.

Born and raised in Buffalo, New York, Thompson was a five-time New York State Golden Gloves champion and participated in the 2008 Olympic trials. He won his first 12 pro fights before being rudely introduced to the politics of boxing. It happened in Pointe-Claire, Quebec, where Thompson was matched against a local fighter, Nicholson Poulard.

When the bell sounded ending the tenth and final round, Poulard’s half-brother, Jean Pascal, entered the ring to congratulate Thompson who took the gesture as a sign that he had won the fight, a foregone conclusion in his mind. Alas, two of the judges differed and Thompson lost a split decision. (Ringside reporter Hans Olson and veteran Quebec judge Pasquale Procopio both had it 97-93 for Thompson.)

Four months later, Thompson found himself in the ring against Sergey Kovalev. The Russian was then in his prime, undefeated and rocketing toward a #2 ranking on the pound-for-pound list of The Ring magazine.

Thompson had no excuses after Kovalev bombed him out in the third round, but it’s worth noting that he took the fight on nine days notice when former title-holder Gabriel Campillo, Sergey’s original opponent, suffered a back injury in training.

Thompson rebounded with three wins, most notably a lopsided 10-round decision over 21-1 Ryan Coyne in Atlantic City, before misfortune struck again. His bout on HBO with Serbia’s then-undefeated “Hot Rod” Kalajdzic, truncated at the last minute from 10 to eight rounds, resulted in another narrow setback. In this bout, Lionell had a point deducted for losing his mouthpiece, without which the contest would have ended in a draw.

Thompson was inactive for the next 17 months, during which he moved to Las Vegas where he found work as a security guard and caught the eye of the big cheese while staying in shape at the Mayweather Boxing Club. He was 6-2 for Mayweather’s Money Team Promotions, advancing his record to 22-5. The last of those 22 wins came on Sept. 28, 2019, in what currently stands as his final fight.

On that date, he scored a big upset, winning a comprehensive 10-round decision over former world title-holder Jose Uzcategui.

Thompson had been a light heavyweight his entire career going back to his amateur days. For this fight, he scaled down to super middleweight (168). He says he shed 30 pounds in a few weeks without being weight-drained after accepting the match, a remarkable accomplishment for a man in his mid-30s.

Thompson says his purse for Uzcategui was $39,000. After the fight, he says, he spurned a $100,000 offer to fight WBC super middleweight champion David Benavidez.

“It wasn’t a fair offer,” he says, “not with a world title on the line. When all was said and done, I might have walked away with $50,000. My life has been hard since birth. I didn’t have a strong family. I have paid my dues and I deserve to walk away from this sport with some money.”

Indeed, his life has been hard. He spent most of his middle school years and high school years in a foster home. “It was the worst time in my life, like being incarcerated,” he says, while acknowledging that it was a blessing in one regard. Down the street was the New Mt. Ararat Temple of Prayer, a nondenominational church where Lionell found a sanctuary.

“B-side” fighters often need to work as a sparring partner to keep the wolf from the door while they wait for the phone to ring. Thompson is no exception. He has sparred more than a hundred rounds with Artur Beterbiev, and a fellow who touches gloves with Beterbiev, even in a simulated fight, certainly earns every penny he makes. “He’s a beast,” says Thompson of the Montreal-based Russian who owns three pieces of the world light heavyweight title and has won all 19 of his pro fights by knockout. “There are no words to describe how hard he hit me.”

Lionell Thompson can currently be found at the DLX boxing gym in Las Vegas where he helps manage the place. Caleb Plant trained there for his recent match with the aforementioned Benavidez and there’s a great irony in that.

Both fought Jose Uzcategui. Thompson had an easier go of it than Plant who toughed out a well-earned decision in a 12-round fight. And for Plant, who purportedly had the advantage of an 8-week camp, it opened the door to eventual seven-figure purses.

Although a few succeeded in shattering the glass ceiling and achieved great wealth (think Muhammad Ali, Sugar Ray Leonard, and Floyd Mayweather Jr), the deck has been stacked against black boxers since the very dawn of the Queensberry Era when John L. Sullivan drew the color line so that he wouldn’t be embarrassed by Peter Jackson. If Lionell Thompson had been active in the 1940s, he would have fit right in with the Murderers’ Row, the term that Budd Schulberg coined to describe a group of outstanding black boxers – (e.g., Charley Burley, Lloyd Marshall, Holman Williams) – who were too good for their own good and were thus never tendered a title shot.

Lionell doesn’t resent Caleb Plant for raking in the big bucks. To the contrary, he is happy for him. “I love Caleb,” he says, “I consider him a friend.” It is the boxing establishment, not any specific person, that has wronged him, making him, by his reckoning, the most avoided boxer in his sport.

In his spare time, Thompson reads the Bible and watches “The Equalizer,” the 2014 original starring Denzel Washington as a retired government assassin turned vigilante. Lionell identifies with Washington’s character Robert McCall, a “psychopathic sweetheart” who wipes out the bad guys as he pursues justice for the exploited.

Thompson’s attachment to the “The Equalizer” is less an infatuation than a full-blown obsession. He’s watched the movie on DVD more than a thousand times. It has cost him at least one girlfriend. He has never been married.

“I don’t believe there is a super middleweight out there who can beat me,” he says. “I know that with the right guidance I can become a world champion late this year or maybe next year. My faith is strong and I believe God will bring justice to my situation.”

That may be a pipe dream. On the day that we chatted with him, he allowed that he weighed 197 pounds. He isn’t ranked in the top 10 at 168 by any of the relevant sanctioning bodies and at age 37 it figures that his peak years are behind him. But if he never captures a world title, he can take solace in knowing that he had a career that harked to the Murderers’ Row and that puts him in good company.

Arne K. Lang’s third boxing book, titled “George Dixon, Terry McGovern and the Culture of Boxing in America, 1890-1910,” rolled off the press in September. Published by McFarland, the book can be ordered directly from the publisher or via Amazon.

To comment on this story in the Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from New York Where Taylor Edged Serrano Once Again

-

Featured Articles5 days ago

Featured Articles5 days agoThe Hauser Report: Zayas-Garcia, Pacquiao, Usyk, and the NYSAC

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoResults and Recaps from NYC where Hamzah Sheeraz was Spectacular

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoFrom a Sympathetic Figure to a Pariah: The Travails of Julio Cesar Chavez Jr

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoManny Pacquiao and Mario Barrios Fight to a Draw; Fundora stops Tim Tszyu

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoPhiladelphia Welterweight Gil Turner, a Phenom, Now Rests in an Unmarked Grave

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoArne’s Almanac: Pacquiao-Barrios Redux

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoCatterall vs Eubank Ends Prematurely; Catterall Wins a Technical Decision