Featured Articles

The Fifty Greatest Flyweights of All Time: Part Five 10-1

The Fifty Greatest Flyweights of All Time: Part Five 10-1

No lengthy introduction to this one; the word count is out of sight. It may be worth your while to take it on in two or three chunks.

No apologies though. These men deserve their due.

One final time, for the sweet souvenir:

This, is how I have them:

#10 -Masao Oba (1966-1973)

Masoa Oba (or Obha), held a strap but never held the legitimate flyweight championship of the world; this did not stop him going on one of the most incredible tears in the history of 112lbs.

It would have been something special to have been ringside on the second of September 1968 when Oba clashed with Susumu Hanagata over ten rounds in what would be his last ever loss in what sounds a wonderful fight. These two would meet again further down the line but first for Oba came a chance to gain valuable experience as a stay-busy opponent for beltholder Bernabe Villacampo. Whoever selected Oba presumably did not keep his job as the Japanese out-worked and out-fought his more illustrious opponent over ten rounds in a non-title fight. The shockwaves resounded throughout the division.

Shockwaves deepened to seismic alarm when Oba was rewarded with a shot at a strap of his own against Berkrerk Chartvanchai. He dominated that fight from the first bell, working with fast pressure and fast hands, showing a narrow leading frame to his opponent, keeping his guard low but mobile. Such was his speed of thought and movement that a jab could be supplanted by an uppercut to the gut or a straight right hand from a suddenly square stance; there were chinks in his armour but taking advantage of them supposed that his thrilling offense could not close that gap. This was not the case against Chartvanchai, nor ever again in Oba’s career.

After two pinpoint lead right-hands broke Cahrvanchai’s resistance in the thirteenth, Oba took on the monstrous Betulio Gonzalez. Their fight was an extraordinary one, exquisitely narrow rounds early being decided by single right hands bought by an active left jab – but the late rounds were war. Oba emerged with a slender decision, contrary to my card of 8-7 for Gonzalez, but contrary, too, to rumors of a robbery.

Oba continued to tear up the division, winning another excellent fight with contender Fernando Cabanela in 1971, avenging himself upon the wild Susumu Hanagata the following year, then stopping Orlando Amores with precision punching before surviving a disastrous first round to stop the great Charchai Chionoi in the twelfth in 1973. It was a divisional massacre.

Perhaps it would have stopped there regardless; Oba had begun planning an assault on the bantamweight division. Alas, it was not to be. Aged just twenty-three his life was claimed in an automobile accident. The similarities between his tragic demise and that of Salvador Sanchez – both dying at twenty-three, both in car accidents – are eerie.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Chartchani Chionoi (Top Ten), Betulio Gonzalez (15)

#09 – Pone Kingpetch (1954-1966)

There was something fragile and beautiful about Pone Kingpetch’s boxing, all movement and the search for proper distance, but there was nothing fragile about the man himself; he was durable and aggressive when called upon.

He took the title from a living nightmare in the ring and a man who should have enjoyed a mighty style advantage over him, Pascual Perez. Perez, who had reigned as king for six years, traveled to Thailand in 1960 and like so many before and after did not find it to his liking. Kingpetch took the title by virtue of a split decision, now seen as controversial in some corners. The surviving footage shows otherwise. The two fought a desperate struggle for territory, dominated in spells by Pone’s smart boxing moves launched from a height and reach advantage so large as to appear comical. Nat Fleischer’s 146-140 card in the Thai’s favor seems not unreasonable.

Either way, Pone put any debate to bed in an immediate rematch which he dominated and won by eighth round TKO. A persistent and sapping right hand to the body dropped Perez’s guard and resistance.

Kingpetch staged quality defenses against Mistunori Seki and Kyo Noguchi in 1961 and 1962 before being blasted out of his title by the great Fighting Harada in Japan. Harada, essentially a turbo-charged Perez, was sensational in taking out the champion but the Thai’s handy lead at the time of the stoppage inspired him to come again. In an immediate rematch in Thailand, Pone reclaimed his title in a fight for the ages. No clash of styles was every more beautifully rendered as Pone found a way amid a storm of Harada leather. It was a deployment as old as the sport itself, a stiff, straight left, a right-hand lead to the body in close, a counter-right to the head. He was arguably a little fortunate in getting the nod, but it was no robbery.

The champion then met yet another great fighter in the shape of Hiroyuki Ebihara who blasted him out in a round and seemingly ended his career. Pone gathered himself once more and squeaked past Ebihara via decision in a glorious past-prime throwback.

That made him a three-time flyweight champion, an incredible achievement. As elegant a boxer as ever graced the division, Pone Kingpetch also brought steel and heart and a right hand to the body Joe Frazier would have given his bad eye for.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Pascual Perez (Top Ten), Hiroyuki Ebihara (12), Fighting Harada (40).

#08 – Chartchai Chionoi (1959-1975)

Chartchai Chionoi, the Thai legend, seemed just another fighter when he turned professional way back in the late fifties; by the time of his retirement in 1975 he stood as a two-time flyweight champion of the world and had contested no fewer than thirteen world-title fights. He was a true giant of the flyweight division and perhaps the first incontrovertibly great pure flyweight we have run across.

Glimmers of his huge potential shone through in his torrid 1963 defeat of Japanese 112lb champion Seisaku Saito in an otherwise bad year. Chionoi’s flirtation with a world ranking was inconsistent and the level of opposition he met equally so. It was something of a surprise then, when upon tempting champion Walter McGowan out to Thailand in December of 1966 he lifted the world flyweight title on a seventh-round stoppage. Chionoi’s strategy was machismo of which a Mexican would have been proud, essentially allowing McGowan to hit him with that cultured left while exacting a terrible tole with his own right. McGown was physically unequal to the task and crumbled not once but twice, the rematch in London especially exemplary of the Thai’s brutal style.

For his second defense, Chionoi matched a man more able to dish out punishment than even he in the form of Efren Torres. The two staged a trilogy in a storm of blood, their first fight, one of the great flyweight championship contests, as savage as anything that can be seen in the modern annals of boxing history, won by the champion in thirteen rounds. A terrible eye-injury cost him the title in their 1969 rematch, but Chinoi returned, mercilessly, thrillingly, once more dominating his brutal opponent with a body-attack now honed to perfection.

But three fights against so vicious an opponent perhaps signaled the end of his absolute prime. In his very next he seemed shell-shocked and vulnerable in dropping his title to Erbito Salavarria.

Even so marred he was capable of foiling the plans of elite fighters, ranked men, and his resume is bolstered by the names of Fritz Chervet, Berkeret Charvanchai and Berabe Villacampo.

A short-lived though devastating peak and some patchy results before and after his two-pronged tear at the division mean the upper limits of the top ten are beyond him, but there isn’t another fighter on this list quite like Chionoi.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Efren Torres (26).

#07 – Pancho Villa (1919-1925)

Perhaps the grinding poverty from which Filipino Pancho Villa rose cannot be understood by a western witness.

Abandoned by his father while just a baby, Villa was raised his mother, who herded goats. As a child he traveled to Manila to make his fortune and fell in first with a scraped together boxing gym and then an American promoter with connections to the uncrowned king of boxing, Tex Rickard. Rickard threw the exotic Villa to the wolves amid some questionable promotion and he was roundly beaten by the excellent Abe Goldstein and the brilliant Frankie Genaro – but Rickard took one look at the delight with which the New York crowd greeted Villa’s free-swinging hard-punching style and saw dollar signs.

When Genaro again bested Villa 1922 but priced himself out of a meeting with American champion Johnny Buff, Villa happily stepped in to fill the void. He had studied carefully and tempered his unhinged style for the American ring. The first round he boxed against Buff was careful and thoughtful; by the seventh Buff was described as “a crimson smear”; in the eleventh his corner tossed the towel.

Four months after besting ring legend Frankie Mason, Villa found himself in the opposite corner to a ring immortal, “The Might Atom” Jimmy Wilde, tempted out of retirement for one last payday in defense of the flyweight championship most still hung upon him.

Villa controlled their contest completely. He out-fought and out-sped the older man from the third through to the desperate ending when he dropped a right-hook from a square stance depositing Wilde unconscious on his face

Wilde was magnanimous in defeat naming Villa a “great fighter who will make a good champion.”

This can be disputed. Already, Villa’s head was being turned by the bigger purses (and meals) that could be had at higher weights. At flyweight he staged three title defenses, the best of them against the excellent Benny Schwartz who he out-pointed over fifteen. His failure to defend against Genaro would be a black mark against his reign but articles were signed for that fight before first one, then the other pulled out with injury. His tragic death at just twenty-three cheated us of a final showdown

Regardless he stormed the United States with a style as violent and irresistible as his fistic descendant Manny Pacquiao and his destruction of Jimmy Wilde, albeit a faded version, carries serious weight of legacy.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Jimmy Wilde (Top Ten).

#06 – Benny Lynch (1931-1938)

We reach a false summit with this inclusion. Seven through ten are debatable with eleven through fourteen but here, at six, we meet our first indisputable member of The Ten. Benny Lynch, the greatest fighter to hail from my home country of Scotland, is a lock.

Born in the Gorbals, a notorious housing scheme in the city of Glasgow, Lynch was plying his trade in the thriving smokehouses and gyms of the Scottish fight scene by twenty-one. He would box almost one hundred and thirty contests. He would be stopped only in his last by which time he was weighing at a pudgy, drink-sodden 131lbs. An iron-born man hailing from an iron-hued city he had a natural talent and aptitude for fighting.

Emerging from the terrible chaos that shrouded the division after the abdication of Fidel LaBarba in 1927, Lynch positioned himself for glory in dusting two elite French fighters tempted to Glasgow for sizeable purses, Maurice Huguenin and Valentin Angelmann. His reward was a crack at a piece of the splintered title against Jackie Brown. Brown, an ironman in his own right, had been knocked out just once five years earlier, a slight for which he had three times wrought vengeance. Having boxed Lynch to a draw up at bantamweight earlier in 1935, experts predicted Brown would keep matters tight once more.

What they witnessed instead was a man possessed grasping his opportunity with both gloved hands.

Lynch was a puncher. Not a darkening one, but nor just a stinging one, as Brown would no doubt attest after swallowing a flush, trapping right hand in the first. Brown got up but he was never again in the fight. Lynch now deployed his left-hook, an even better punch, and Brown was sent to the canvas thrice more in the first. Keeping count of the knockdowns in the second round is difficult; the referee finally rescued the hapless Brown and Lynch had arrived.

Elite flyweights Pat Palmer and Syd Parker followed in the trail of destruction, both succumbing to stoppages, the former falling short in a crack at Lynch’s strap. Despite his dominance, the title picture remained confused. Lynch righted it early in 1937 when he bested Small Montana, the only other man on the planet with a claim to the flyweight championship. Their fight was not one-sided. Montana was perhaps the only man to really stretch the primed flyweight Lynch and according to the United Press report he stretched him all the way to the final round where their toe-to-toe battle was settled in the Scotsman’s favor.

He swaggered in the ring and launched sudden two-fisted attacks that sometimes seemed to have no end in front of crowds of forty-five thousand. He had it all.

In October of 1937, already beginning to slip, he met the murderous punching Peter Kane, then 42-0, my selection as the division’s #2 puncher; Lynch took what he had to give, doubled it, and banged him out in thirteen rounds. Harder, faster, better. But he would never make the flyweight limit again. Alcohol had overtaken him.

By 1938 his career was over. In 1946, just thirty-three years of age, Benny Lynch was dead.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Peter Kane (16)

#05 – Frankie Genaro (1920-1934)

Olympic Gold medal winner Frankie Genaro may have been a genius. We have to be careful about hanging such a tag upon him as footage is at a premium, but nothing I have ever read has dissuaded me from this thinking.

His brilliance was most crystallized in his three-fight series with the puncher Pancho Villa. Just as the fights between Pone Kingpetch and Fighting Harada represent a special clash of styles so too do these two seem to have sapped the far reaches of excellence from one another although here there was never any doubt as to who was the better; Genaro took the decision from Villa on all three occasions.

The first meeting between the two was staged in July of 1922 and Genaro took full advantage of Villa’s green streak. In possession of a clean style advantage over his ultra-aggressive foe, Genaro slipped and countered his way through a relatively one-sided fight to take the decision. In their second contest fought just two months later, Genaro was again dominant, this time buzzing the Filipino with a right hand before unleashing his left hook to romp home once more, “a perfect combination of skill, superb boxing ability, speed and cool” according to one ringside reporter. This last cannot be underestimated. A hundred-fight career brought its share of disaster down on Genaro’s head but his temperament and the resulting generalship was never in doubt.

The two met for a third and final time early the following year and this time the fight was scheduled for fifteen rounds and was much, much closer. Genaro suffered a deep cut under his left eye and both fighters ended the contest smothered in his blood; but it was Genaro, who dominated the final three rounds with quick-handed forays into his opponent’s sphere of influence followed by slick retreats barracked by counterpunches.

Despite his domination of their trilogy, Villa remained a thorn in Genaro’s side, losing to him but somehow beating him to fights with both Johnny Buff and Jimmy Wilde. Villa then failed to defend against his old tormentor. Their third fight is close enough to wonder if Genaro would have slipped over the line against the Pinoy puncher in a title match, but he certainly would have started a favorite and unquestionably deserved the shot.

Genaro’s great career was defined by Villa but not limited to it. He also defeated many of the finest names from a stacked era, many of whom will be familiar to readers of this series. Valentin Angelmann, Ruby Bradley, Emile Pladner, Steve Rocco and Frenchy Belanger all fell to him at one time or another (though Pladner also once defeated him with an exquisite sounding liver-shot). It adds up to one of the most rendered resumes in the history of flyweight boxing.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Emile Pladner (37), Pancho Villa (Top Ten)

#04 – Midget Wolgast (1925-1940)

Midget Wolgast is my favorite flyweight and one of the most outrageous geniuses in fistic history.

His boxing was a conflation of dizzying defensive wonderment and mobile attacking brilliance. He feinted his opponent forwards and then moved off the center line, his reactions to any offensive foray a deft slip of the head, but his own offense was what differentiates him from other great defensive wizards. Wolgast, who couldn’t punch to save himself, was unequalled at firing off blows while on the move. His bread and butter was a shrill pop of a jab that he could land whatever angles his balletic movement inflicted, and as an improviser he was second to none. When the time came to scrap, he moved in on his man, head working like a cat about to strike, deploying a swarming body attack of dizzying variety. He was a jazz musician in a pair of boxing gloves, and domination was his art.

This combination made him a disaster for a generation of flyweights. Willie Davies slumped to multiple defeats against him, their rivalry perhaps the greatest in flyweight history as Davies time and again pushed his opponent to the very brink but succeeded in winning only one of their seemingly endless stream of combats.

Even the beginnings of his excellence are too long to tell but his 1927 win over Izzy Schwarz is as fine a place as any. Schwartz was an experienced ring veteran, only moths away from his own victory over Willie Davies and a year from his victory in an NYSAC title fight, but he couldn’t do anything with Wolgast who, though still a teenager, clearly out-pointed him. Billy Kelly, Ernie Peters, Phil Tobias, Ruby Bradley, Johnny McCoy, Jackie Brown – the list of made men he befuddled starts here and just rolls on and on. In fact, no fighter on this list defeated more Ring or TBRB ranked contenders than Wolgast. That bears repeating – Wolgast defeated more ranked men than any other fighter accounted for on this list, which is the same as saying anyone.

What keeps him from the top three is the brute fact that he never won the lineal title. Wolgast had a chance, too, albeit against Frankie Genaro. Both Genaro and Wolgast held a strap meaning neither held full recognition. They met in 1930 for all the marbles in a fight that could and perhaps should have been the greatest flyweight contest of all time – but failed to deliver. In a turgid, nervous affair, Genaro scored with a beautiful right hand in the second which closed Wolgast’s eye and set the fleet-footed magician on the run. He boxed and Genaro brought pressure, Genaro closing the stronger of the two to split the judges three ways for the draw. There would be no rematch.

He did lift a strap against the deadly Black Bill aged just nineteen, an incredible feat, but one that isn’t quite special enough to ghost him into the company of the three greatest champions in flyweight history.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Corporal Izzy Schwartz (50), Black Bill (36), Willie Davies (11).

#03 – Pascual Perez (1952-1964)

Pascual Perez was one of the great champions at any weight, winning the title and then successfully defending it on nine separate occasions. This was a part of his incredible 53-1-1 run, stretching from his first fight in 1955 and up to 1960, when the great Pone Kingpetch finally unseated him.

Nor was Perez protected by the Argentine tradition of giving out draws to favored sons. Perez came up hard, boxing under different names and in different cities. Not until he had traveled to Japan and unseated then champion Yoshio Shirai did he become a true hero to his people and a regular at the Estadio Luna Park in Buenos Aires.

The night he took the title in Japan, Perez weighed a mere 107lbs although standing just under five feet tall he was in no way underweight. Perez would never scale the full poundage of the flyweight limit in his championship career, though he embodied the style and did the damage of a much more physical man. A jab both probing and thudding was primary but he was happy to lead with the right hand and did so often; his wheelhouse was the inside, where he kept low and slugged to the body before deftly moving upstairs with the same savage precision. His demeanor in the ring was one of fierce attention.

That attention laid low numerous world class flyweights. When Shirai tried to fight fire with fire in their third and final match, Perez retired him with a right hand of fearsome construction. The same punch rudely dispatched the highly ranked Young Martin who was counted out tangled in the ropes like a drunkard. Dai Dower, ranked number two, lasted just seconds before a right hand from a square stance dropped him for the count. Men who lasted the distance often wish they hadn’t, and Perez travelled to Japan, Venezuela and The Philippines to make them feel that way.

His was the most complete championship run in the history of the division.

Almost.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Yoshio Shirai (23)

#02 – Jimmy Wilde (1911-1923)

Jimmy Wilde is number two.

Reader expectation has been an interesting aspect of this series and it is likely no aspect of reader expectation will be more well-worn than that of Jimmy Wilde as the greatest flyweight in history. He was ranked as such by Nat Fleischer, Charley Rose and Herb Goldman. Why then, is he not rated as such here?

Well, Wilde was inarguably the greatest ever to box at flyweight but my argument is he was not the greatest ever flyweight boxer. The true answer, as always, is criteria, and mine can be read in Part One, but the most important aspect to be remembered here is that this list “only considers fights that took place at flyweight or just above.” It is a flyweight list in the truest sense of the word.

What Wilde did against opponents weighing in above the flyweight limit is absurd. His victory over Joe Conn, a featherweight on a hot streak, is perhaps the single greatest win in boxing history. The temptation to credit him in this division while weighing twenty pounds less than Conn is enormous; but it wasn’t a flyweight match – it was a featherweight contest. In unpicking the history of the 112lb division then, it has no relevance.

As for Wilde’s championship legacy at flyweight, tracing it can be difficult. For some it can be counted from 1914 when he lifted the European flyweight title against the even smaller Eugene Husson, a fight also billed for something called the “gnatweight title”. This claim is muddied by Wilde’s fellow Welshman Percy Jones, who held the IBU flyweight title at the same time; he then lost that title to Joe Symonds. The Symonds claim was in turn strengthened over Wilde’s because he was able to defeat the man who stopped Wilde in 1915, Tancy Lee. When the gnatweight title fell by the wayside the European title Wilde held remained just that in terms of lineage while the IBU title, held by Jones and Symonds, morphs into the flyweight title – meanwhile America recognized no meaningful flyweight champion, though a “paperweight” title did receive fleeting attention.

This mess was born of a semi-recognized division which was as geographically moribund as any, ever. Within this division, Wilde’s early involvement in competition for such titles does speak to his elite status, but he cannot be named the best flyweight in the world until 1916, especially not in the light of his knockout loss to Lee in 1915. From 1916 to 1920 though, Wilde was the Don and the single most significant flyweight in history as he became the overseer of the division’s transition to legitimacy. His destruction of Sid Smith in eight rounds at the very end of 1915 was the true beginning of his evisceration of the poundage and when he later turned the same trick in just three his confirmation as prime was complete. In between he forced Symonds to quit after twelve before avenging himself upon the still red-hot Tancy Lee that June. When he hosted and dominated American flyweight Young Zulu Kid in December his claim was beyond dispute. The first undisputed flyweight world champion had been born.

Between 1911 and 1920, Wilde lost to just one flyweight in Lee and he butchered his nemesis in the return. It is possible to be ultra-critical in pointing out that Wilde’s record of 1-1 against the best fly he ever fought is perhaps a little unsatisfactory, but Wilde settled their dispute in that second fight. This streak is the hottest of the hot and is paralleled only by the very greatest fighters in history; certainly, no flyweight ever recreated it. Wilde did all of this boxing with a savage abandon and in a style recreated by no fighters either before or after him, a style birthed by his power, his heart and his granite chin.

But questions concerning the depth of his opposition remain and his record in true championship fights, impressive in a generous reading at 7-1, pales in comparison to our divisional number one.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Sid Smith (44), Joe Symonds (43), Tancy Lee (22).

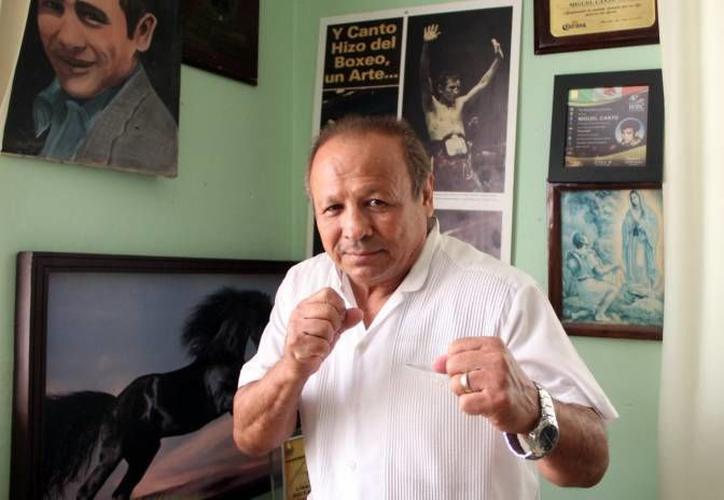

#01 – Miguel Canto (1969-1982)

15-1-1 are Miguel Canto’s corresponding numbers in lineal championship fights.

Pongsaklek Wonjongkam managed more defenses but readers of this series will be familiar with the problems his record presents – Canto racked up his numbers in perhaps the deepest flyweight division that has ever been mustered. Were he a heavyweight he would be lauded as the third great alongside Muhammad Ali and Joe Louis.

Canto first grabbed attention in 1971 when he defeated Alberto Morales, a capable and durable little fighter who was pitted against the same massed ranks of Mexican flys that Canto had to negotiate. A world-level fighter he held the Mexican title and would go on to defeat future champion Guty Espadas, but in three attempts he couldn’t undo the little magician. Canto had named himself the exceptional talent out of Mexico and a title-challenge was his reward.

But the title was in the possession of Betulio Gonzalez, an exceptional talent, as readers of Part Four will remember; Canto learned his final lesson on Venezuelan soil against Gonzalez dropping a close, questionable decision. The fighter that emerged from that majority decision defeat stood on a rare peak.

In 1975 Canto established a lineal claim in as dominant a fashion as any fighter, ever. In January, March and May of that year he defeated the three other most significant flyweights in the world: Shoji Oguma, Ignacio Espinal and Betulio Gonzalez. These five short months shape his flyweight legacy.

Against Oguma, a surging southpaw pressure-fighter who had the great gift of timing his rushes to cause maximum inconvenience to his opponents, it was the night of the right hand, a punch the Mexican used to tattoo his opponent’s head, gathering points. In his rematch with Gonzalez, Canto put on what may have been the greatest left-handed clinic in boxing history, which he repeated in their third and final match. His jab and hook hit the heights of pure rhythm and despite the majority decision won by distance and at a canter; no result could have more firmly underlined the enormous strides he had taken since their first fight.

Oguma, who Canto defeated three times in total, was horrified by that first decision loss questioning, much like Dick Tiger or Jake LaMotta before him, how he could have lost if he hadn’t been hurt? He reveals in this remark Canto’s great weakness. He never could punch, and of his swathe of title defenses only one was won on a stoppage.

But Canto wove this weakness into genius. The most interesting champions are always the ones who build upon their shortcomings and Canto is perhaps the shining example. When you can’t hit, every punch matters; Canto’s solution did not call for the wild stylings of Nico Locche nor the poor economy of Willie Pep. He riffed on technical excellence and you have to watch him carefully to see the magic as he gave ground in ever decreasing increments to slowly take control of the range or when boxing a great fighter like Betulio Gonzalez so slightly off the line that Gonzalez fights the whole fight as though he were on it. His elegance in taking his greatest failing and designing a fight that meant it just didn’t matter is more beautiful, more storied, more layered, than any puncher trying to trap a crafty contender onto a right hand.

But there was Mexican in him too. Past prime Canto took on a future champion, the puncher Antonio Avelar and went straight into the trenches with him. Canto was a fine infighter and the instincts of his blood were intact.

That fight was Canto’s final fling as a genuinely great fighter, and he had already lost a step. He lost his title to Chan-Hee Park in 1979 and although he was arguably a little unlucky in the return bout out in Japan, his time had passed. He had all but cleaned one of the truly great divisions.

That’s what truly great fighters do.

Other Top Fifty Flyweights Defeated: Gabriel Bernal (46), Shoji Oguma (31), Betulio Gonzalez (15).

For those of you who have read this series from first to last, I thank you.

Check out more boxing news on video at The Boxing Channel

To comment on this story in The Fight Forum CLICK HERE

-

Book Review4 weeks ago

Book Review4 weeks agoMark Kriegel’s New Book About Mike Tyson is a Must-Read

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoThe Hauser Report: Debunking Two Myths and Other Notes

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoMoses Itauma Continues his Rapid Rise; Steamrolls Dillian Whyte in Riyadh

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoNikita Tszyu and Australia’s Short-Lived Boxing Renaissance

-

Featured Articles4 weeks ago

Featured Articles4 weeks agoKotari and Urakawa – Two Fatalities on the Same Card in Japan: Boxing’s Darkest Day

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoIs Moses Itauma the Next Mike Tyson?

-

Featured Articles2 weeks ago

Featured Articles2 weeks agoBoxing Odds and Ends: Paul vs ‘Tank,’ Big Trouble for Marselles Brown and More

-

Featured Articles3 weeks ago

Featured Articles3 weeks agoAvila Perspective, Chap. 340: MVP in Orlando This Weekend